More About the Times

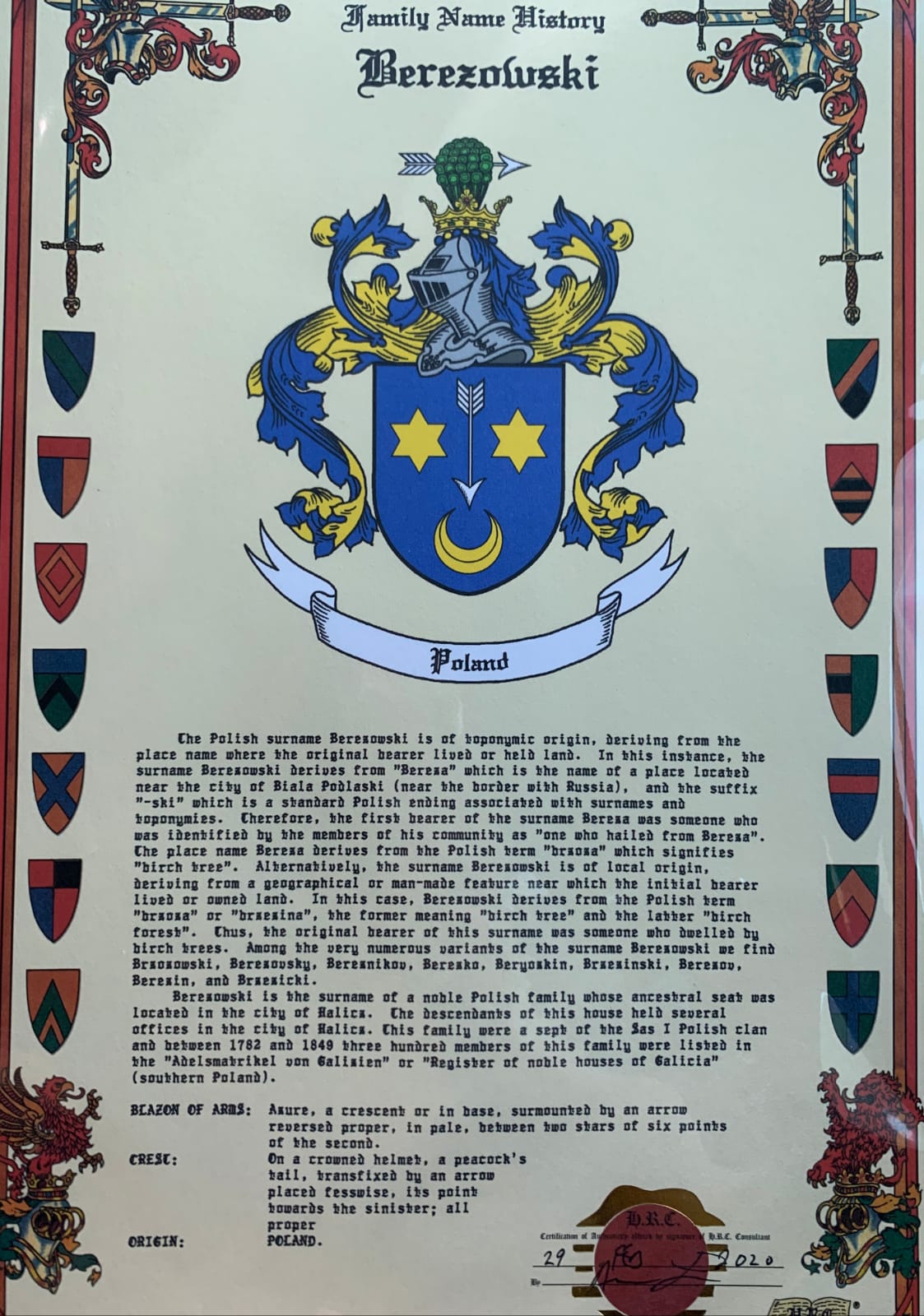

Coat of Arms

Berezowski family coat of Arms, endowed to Anna’s ancestor Samuel Berezowski by King Jan III Sobieski (1629-1686), as she relates in the first chapter of her diary.

Courtesy of Drs. James and Eric Stelnicki.

Polish Eagle

This is the age-old symbol of Poland. Anna refers to it often, praying for her threatened homeland or swearing her promises and love on it. Her family’s stone statue of this eagle reached a bloody end both literally and figuratively, as you’ll see.

Frankish Style Bible Cover

Co-editor John or Jack, Anna’s direct descendant, was inspired by her description of the Frankish Bible cover she salvaged from flames. The central carving, though, is not religious but rather after an illustration of 13th century French love poems.

Mixed media sculpture by John A. Stelnicki, based on authentic historical objects.

Tadeusz Kościuszo

A great Polish hero (1746-1817), he fought under General George Washington in the American Revolutionary War. He returned to Poland to organize uprisings against Russian domination.

Portrait by Karl Gottlieb Schweikart

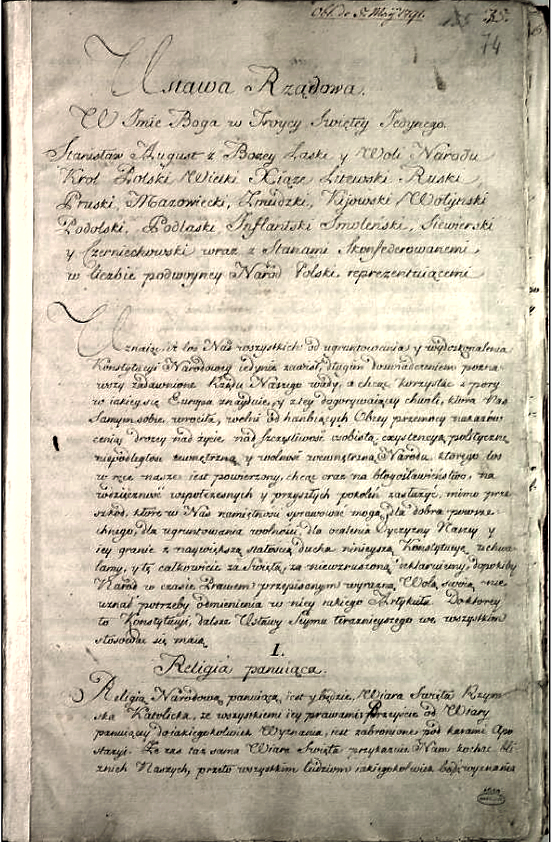

Third of May 1791 Constitution

This is the opening page of the first modern written constitution in Europe. It intended to abolish the nobility’s absolute domination townspeople and peasants. Anna, although a noblewoman, confides to us in her diary how she sympathised with its supporters. But she was forced to pretend otherwise to save her life.

Horse-Drawn Carriages

This scene of the center of Warsaw at Anna’s time shows the type of carriage she often rode in. This painting captures the look of Warsaw then as well as the attire of the coachmen and some of the townspeople.

Holy Cross Church by Bernardo Bellotto

Stanislaw II Augustus Poniatowski

A controversial figure, he was the last Polish monarch. A former lover of Catherine the Great, he’s called by Anna’s aunt « a berry beneath the Empress’s foot. » Discover why.

Stanislaw II August by Marcello Bacciarelli

Catherine II “The Great”

A former Prussian Princess, at 16 she married a cousin who would become Peter III of Russia. She later assumed full control, continually expanding Russia’s territory, including taking over Poland. You’ll see how Anna was caught up in the bloodbaths.

Portrait by Alexandre Roslin

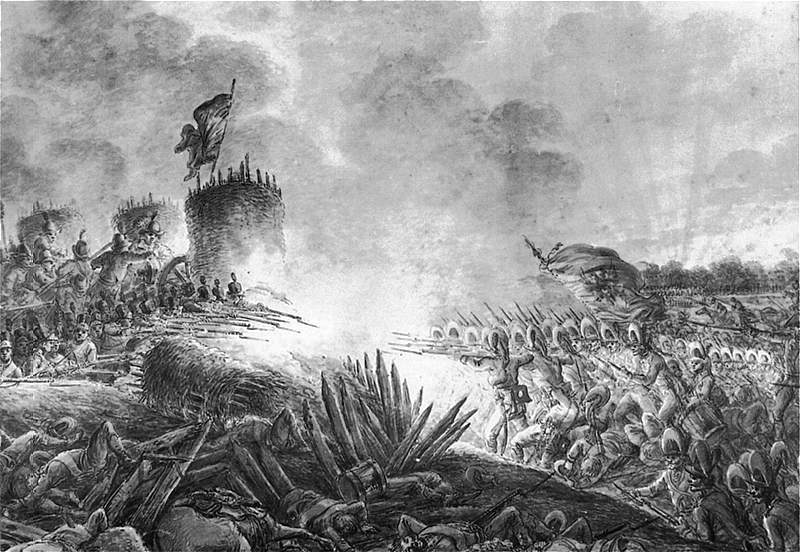

Kościuzsko Uprising

He led this desperate 1794 uprising of Polish patriots against the more powerful Russian forces. Here you can see peasants rallying around their leader and brandishing scythes.

Count John Stelnicki gave up his title and became Pon (citizen) Stelnicki to fight for this cause.

Detail of Battle of Raclawice by Jan Matejko

Battle of Praga 1794

This was one of the most tragic events of the Kościuzsko uprising.

Anna and her child were living in this east suburb of Warsaw when it was massively attacked by Catherine II’s Russian forces on 4 November 1794. Armed Polish patriots rose up against Russian forces. Read how Anna barely escaped to tell her blood-curdling story.

Battle of Praga by Aleksander Orlowski

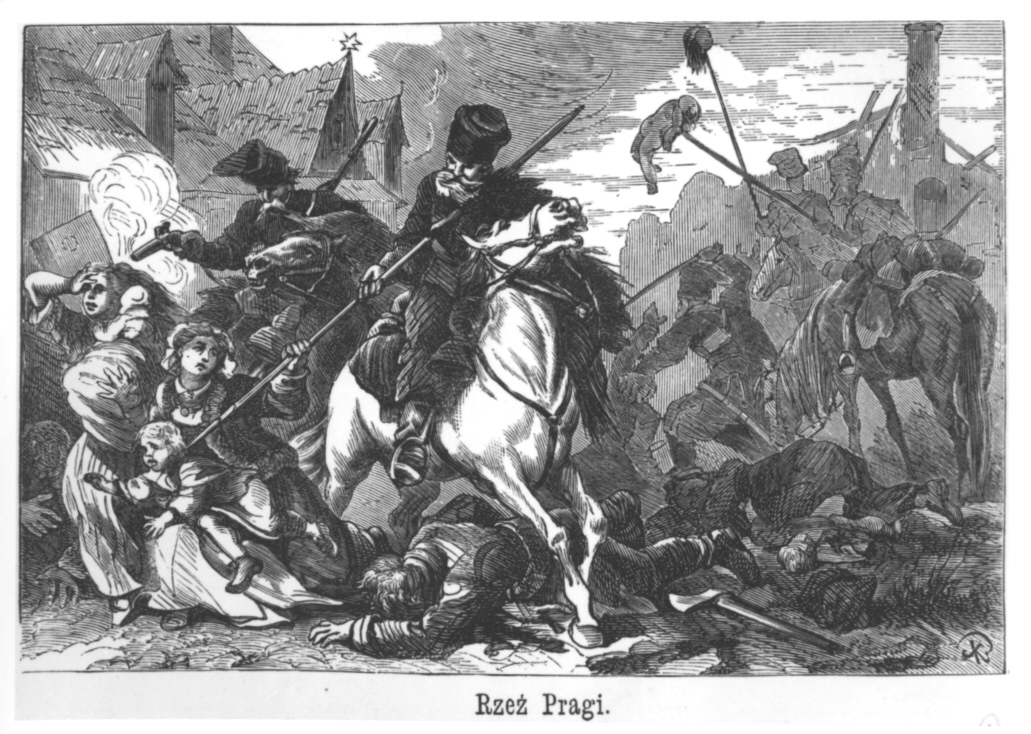

Episode from the Slaughter of Praga

The Russia army marched into Praga and literally murdered most of its civilian population, including helpless old people, not even sparing domestic animals.

The invaders set fire to many wooden structures in town and to the bridge that Anna’s carriage was on. Read her terrifying first-hand account.

Episode from Slaughter of Praga by Aleksander Orlowski

Scene from the Slaughter of Praga

Polish patriots lost the Battle of Praga. This woodcut shows the enemy’s ensuing massacre of civilians, including women and children, that Anna doubtless witnessed. How she (and her diary!) survived these horrors is a miracle. It is unimaginable how traumatized she was. She stopped writing shortly afterwards.

Scene from The Massacre of Praga, 19th century woodcut by unknown artist after Juliusz Kossak

18th Century Dress with Stays

On a lighter note, French fashion set the vogue among Polish aristocracy. Anna wore dresses like this, with stays. What were stays? Well, the two sides of a corset that was supposed to compress a woman’s upper body into a cone shape. Ivory, whalebone, metal or wood strips were inset to lift the bust, trim the waist, hold the shoulders back, and create a smooth support for the overgarment, which Anna calls her gown. This type of clothing had to be laced up the back; hence noblewomen’s need for servants, as they couldn’t get dressed by themselves.

No wonder Anna didn’t seem to regret losing her stays in the snow!

King’s Thursday Dinner

This boisterous scene illustrates some of the fashion and attitudes likely to have been seen at the most important social event in Warsaw. King Stanslaw August hosted these extravagant events on Thursdays, inviting Warsaw’s upper crust. See how Anna, from her farmgirl-at-heart point of view, describes attending one of these functions with her sexy cousin Sophia and the notorious Madame Sic.

Print by unknown artist

Great Assembly Hall of Royal Palace

The main banquet hall where, among other events, the King’s Thursday Dinners were held, particularly in the winter months. This palace or castle was destroyed during World War II but reconstructed according to original plans. It can be visited in Warsaw now.

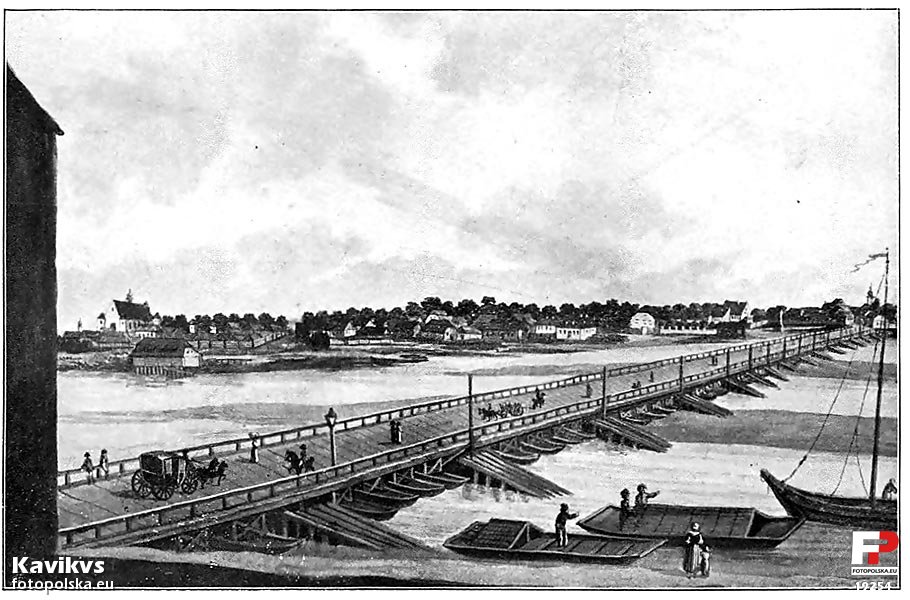

Ponińsky Bridge

This was the bridge that Anna escaped over while it was being burned down behind her with people plummeting to their death, as she says, « like drops of water. » It was the only bridge in Warsaw — a wooden pontoon bridge suspended from floating barges. Warsaw has many bridges now, but none are in the exact place of this one.

Print by unknown artist courtesy of the Polish Historical Society, Warsaw