Iris’s Preface

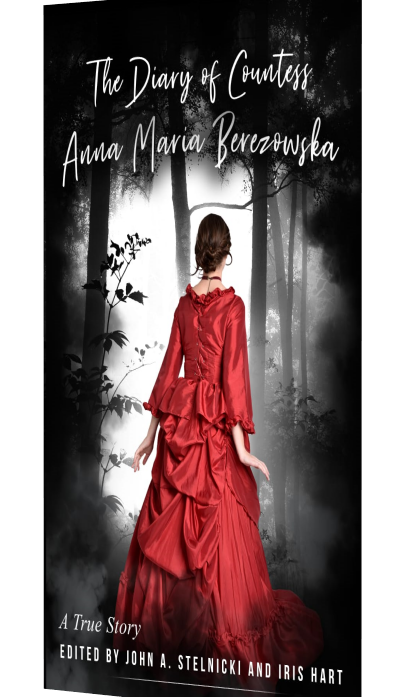

John Stelnicki is my best friend from my long-ago San Francisco days. He was overjoyed when James Conroyd Martin’s historical romance, Push Not the River, based on his ancestor Anna’s diary, was first published in 2003.

After reading Push Not…, I was curious about the original and asked John if I could see it. He willingly complied, and the next time I visited him in San Francisco, he gave me a three-inch-thick cardboard binder containing 257 pages photocopied from crinkly yellowed papers that he typed up over 60 years ago!

Despite the difficulty reading faded typescript and errors in syntax, spelling, and chronology, I couldn’t put this text down. The candid spirit emanating from this young woman’s words, even after being translated mainly from 18th century Polish, touched my heart. From teenage innocence she was unwittingly thrown into situations of unbelievable physical and emotional violence, yet her hopefulness endured. As I watched her mature over a four-year period, I felt as though I knew her in ways that I don’t even know people in my immediate surroundings.

Immediately after reading this draft, I wanted to do everything in my power to help John get it published. He wholeheartedly agreed to accept my editorial aid. This has been a 10-year-long project, which is at last reaching its fruition with this electronic edition and imminent paperback publication.

As an enthralling read, The Diary of Countess Anna Maria Berezowska has got it all: love, deception, intrigue, adventure, suspense, war, thievery, murder, sex… Yet what grips me most is Anna’s multi-faceted personality, her acute observations, the originality of her metaphors ranging from earthy to sublime, her determination, her tenderness, her spontaneity, her sense of humor.

Anna’s state of mind evolved from pure naivete into a tempered acceptance of her world with all its restrictions, contradictions, inequities, and cruelty. As her inner strength grew, she miraculously avoided falling into cynicism or resignation.

Often while editing her writings, looking for synonyms or clarifying certain descriptions, for example, I felt a connection with Anna, like she was communicating to me exactly what she intended to say. John has also frequently experienced that same phenomenon.

So, from her sheltered life as an aristocratic country girl with a haughty edge, uncontrollable circumstances brutally plunged Anna into situations that could have destroyed someone with lesser resilience and will. For me, it’s been fascinating to follow her development as well as her burgeoning consciousness of an unjust class, political, and gender-role system.

At the beginning, when full-length mirrors and two-storied dwellings still impressed her, Anna seemed impatient and disdainful of workers and peasants. But as time went on and she found herself embroiled in life-threatening plights, she grew in tolerance and compassion toward all decent human beings regardless of their social status. I was fascinated by how these changes in her viewpoints emerge from the pages she wrote over the tumultuous period from 1791 to 1795.

Minute observations about her layers of clothing and expected decorum, about customs and superstitions, about sensations in parts of her body made her 18th-century spirit come alive for me. She was a noblewoman striving to overcome a woman’s helplessness concerning her fate and finances. She confided in her diary what she couldn’t say to anyone she knew – radical and unacceptable ideas about social hierarchies, organized religion, arranged marriages, childrearing customs…

So many passages strike me as poetic, such as Chapter 7, “Confronting Eternity,” wherein Anna compares her ravaged body to that of a dead leaf whose sap has left but whose form remains.

In marked counterpoint to Anna, there is an array of vivid characters I personally could never have invented: Walter, her savage oppressor; John, her mercurial true love; Lutisha, the toothless, wizened, steadfast housemaid; Countess Stella Gronska, Anna’s severe widowed aunt who secretly harbored sympathy for the Polish rebels; and Stella’s daughter, the unforgettable Cousin Sophia – lustful, scandalous, conniving, manipulative, a blot on the family’s respectable image. Excerpts from Sophia’s diary, periodically interspersed in bold italics, would surely in themselves be deemed “for adults only.”

I have taken the liberty to occasionally modify the order of Anna’s narrative so that it’s easier to follow. (Sometimes she didn’t have a feather, ink, or paper for a long time, and when later she did, she jotted down remembrances as they came to her, not necessarily in chronological order.) All in all, the words and expressions John and I have agreed to use are fully respectful of what we feel to be Anna’s wishes.

Also, we have chosen to use American English for first names and spelling. And we have divided the work into numbered chapters, which obviously were not in the original. John and I delighted in naming each chapter, sometimes with actual words from the text, sometimes following our own whims and impressions.

I’m continually astounded by the uniqueness of so many of Anna’s comments and hope that our readers will react likewise. Here are just a few examples:

“Her toothless mouth reminded me of an old turtle snapping to bite one’s finger.”

“…when the princess hit his ear with a pendant-pearl as large as a sow’s eye.”

“Her angelic spirit… has become a callous lump of sewing and reading.”

“I was so hungry… evil spirits could find no room for fear in my soul.”

“Her eyes were like two black berries gliding forth from her face; they looked like they were hanging suspended from her eyelashes.”

“She coughed away the sorrows in her voice.”

“My legs turned into two strands of wool attempting to support an iron bell.”

“My son and I must be only a safe droplet on a rock at the side of a fast-flowing river of turmoil.”

“My body is thick and numbed from exposure to the heavy sense of death in others.”

“I could feel invisible vapors rise from my head and breast, then pour onto the floor, spraying up like the plumes of water from the cornucopia of a fountain of cupid.”

“Sophia’s eyes glowed as though they were of polished glass… [and her] outstretched arms flew around me more swiftly than the jaws of a snake…”

Throughout her diary it’s evident that Anna believed that she and her writings survived countless near-fatal incidents so that she could share her thoughts and feelings with posterity, and so that others may learn from them.

My involvement in this publication has been a humbling experience — being immersed in times and circumstances so alien to my own, yet where quests for love, respect, power and security, although taking different forms, are essentially the same as ours. Above all, I am grateful for my bond with Anna, a truly remarkable person with whom I can resonate.

Iris Hart

Paris, 2020

For More Information:

Send Us an Email

Need more information about the book or the editors? Simply want to share a thought with us? Then please email us at countessanna1791@gmail.com

See Us on YouTube

For interviews and fantasy, please see YouTube channel « The Diary of Countess Anna »